Exceptional Works: Chico da Silva

Behind the Fantastical Paintings and the Rediscovering of the Brazilian visionary, Chico da Silva.

Weekly writing about the art market and the convergence of art and technology. By day, I’m a partner at the Robert Fontaine Gallery and a data science consultant. By night, I write Artxiom, ideas at the intersection of art, technology, and finance.

If you haven’t subscribed, join today by subscribing here:

Exceptional Works: Chico da Silva

“The drawing is what the hand gives and the color is what the details ask for. A house is engineering, while painting is autonomy.”

—Chico da Silva

Chico da Silva

Untitled, 1971

Gouache and Mixed media on canvas

Signed and Dated

20 x 28 inches

Framed: 21.25 x 29.25 inches

Provenance

- Private Collection, Maryland

- Collection of Celso Diniz, Brazilian Diplomat

- Gift of the Artist

Untitled (1971) is an intricate work by Brazilian-born artist, Chico da Silva (1910–1985). Featuring fantastical creatures in a dreamlike setting, the painting reflects not only da Silva’s unrivaled imagination but also expansive study of his indigenous roots and the Amazonian flora and fauna in his native Brazil.

In the 1960s, the fantastical paintings of Chico da Silva were wildly popular in Brazil and beyond. Da Silva had become one of the first Brazilian artists of Indigenous descent to achieve national and international recognition. By the time of his death from alcoholism in 1985, his fame had faded away, and the same art world that had put him on a pedestal for his unique style was questioning the authenticity and autonomy of his work. Now, after interest for his work has resurfaced among collectors and curators, scholars are starting to revisit Chico’s work and reexamine the questions around authorship and autonomy that were attached to his oeuvre.

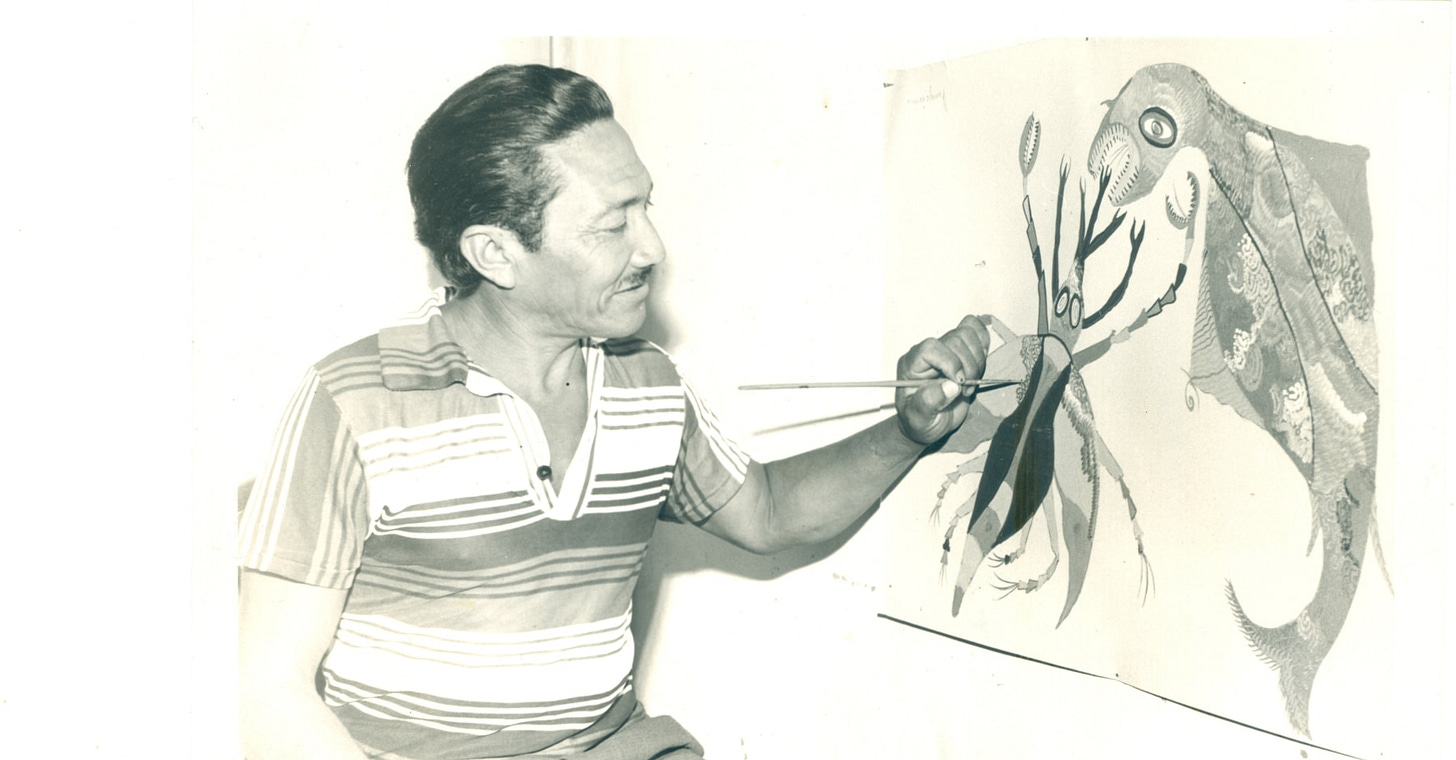

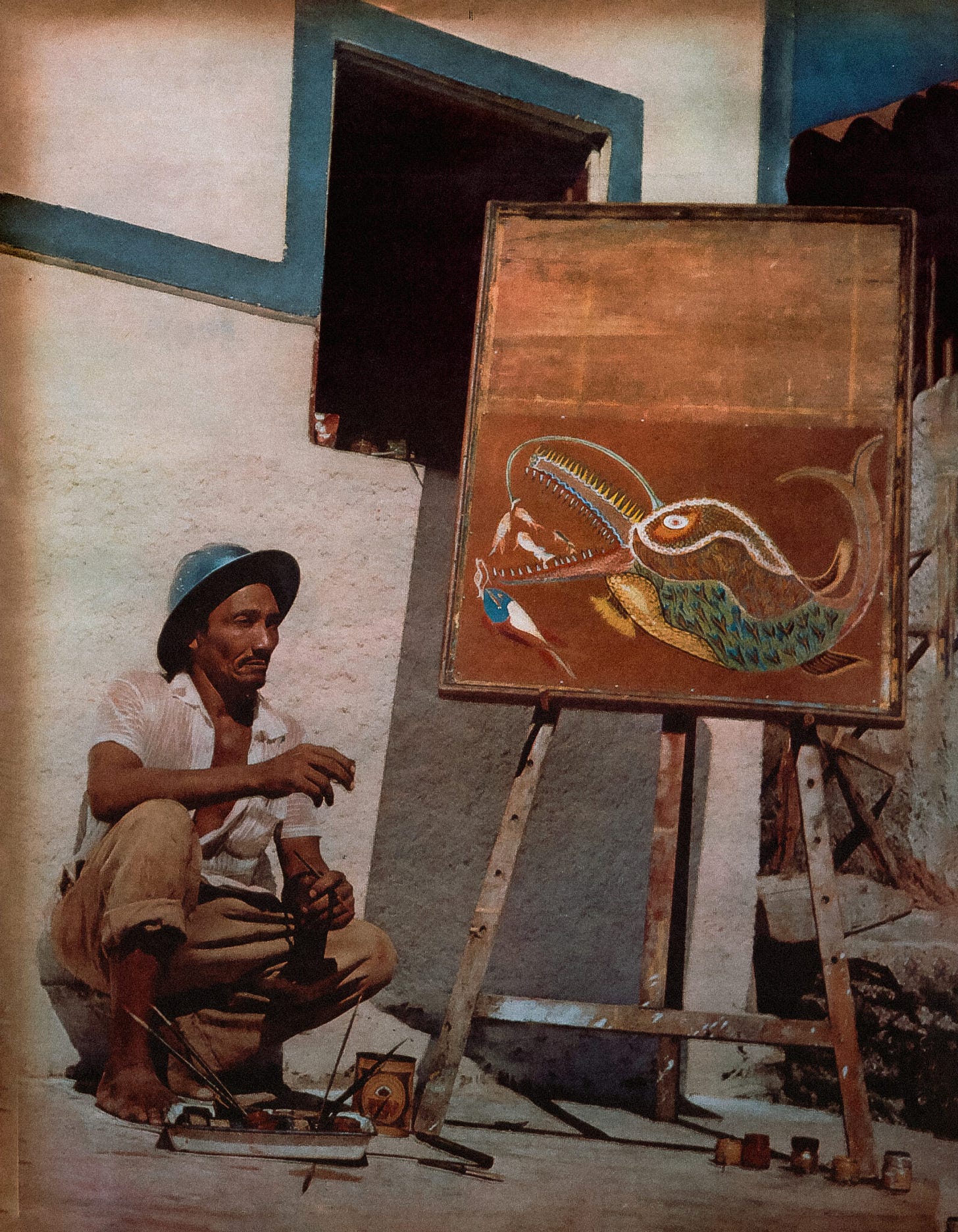

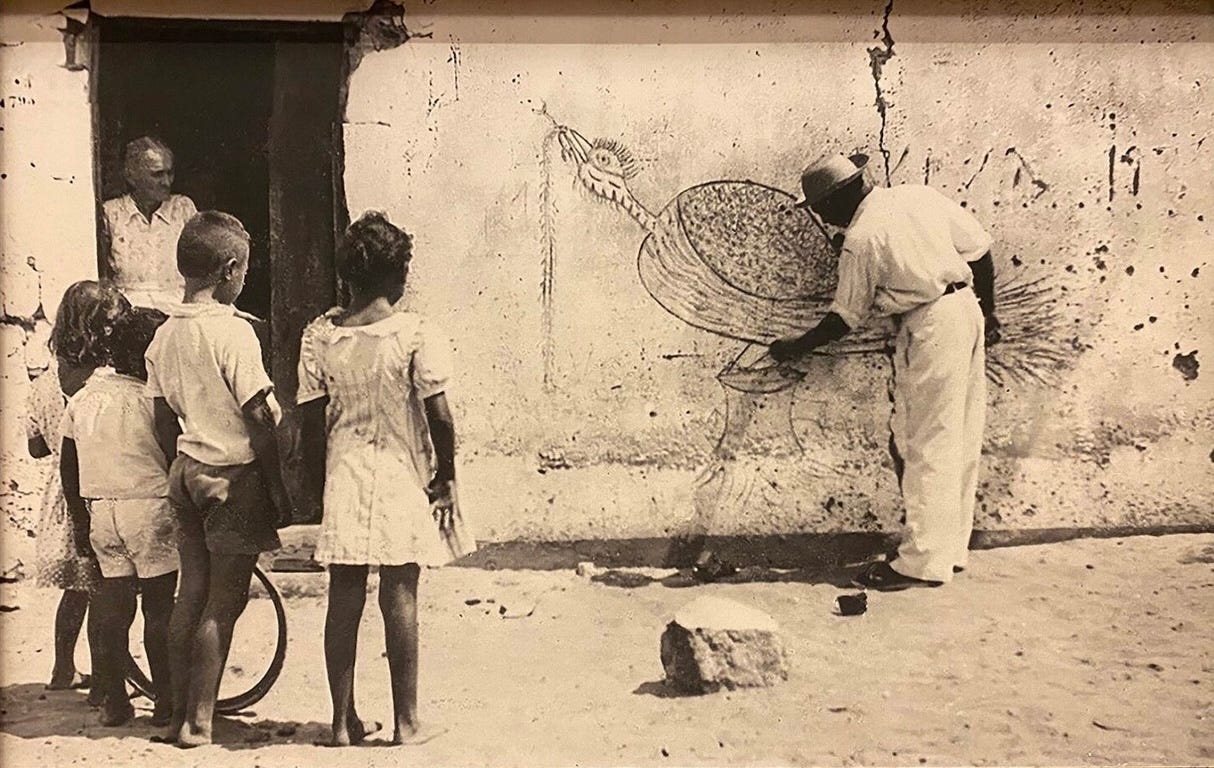

Francisco ‘Chico’ da Silva was born around 1910 to an indigenous Peruvian father of Asháninka origin and a Brazilian mother from Ceará in the Northwestern state of Acre, Brazil. His childhood was shaped by growing up in the Amazonian rainforest before settling in with his mother in Pirambu, a poor neighborhood in Fortaleza, Brazil, after his father’s death. By 1940, Chico had started to paint murals using charcoal (Figure 5), which caught the attention of Swiss art critic, Jean-Pierre Chabloz, who soon became Chico’s patron, introducing him to new materials to paint on like gauche, paper, and canvas. Chabloz was instrumental in facilitating widespread recognition for the painter, who ultimately ended up representing Brazil in the 33rd Venice Biennale in 1966.

Reconsidered today, Chico’s exuberant, elegant, and sophisticated paintings break through the oppressive categories to which they were relegated once, such as naive and popular art. Da Silva developed a distinct visual vocabulary which included representations of mythological or enchanted creatures influenced by the Amazonian fauna and his wild imagination, made surreal through the use of bold colors, intricate lines, and vivid patterns. This approach to painting allowed Chico to merge the life in the poor neighborhood of Pirambu with the dreams and fantasies locals shared. It is not surprising that Chico started to integrate his community into the making of his increasingly in-demand work. Soon, da Silva established the Pirambu School, a workshop in which local artists and curious neighbors learned Chico’s technique and worked as paid assistants. It became a communal system that while it helped with the production of Chico’s work, it also helped in adding important contributions to Chico’s own visual language.

From our current point of view, the Pirambu School seems like a radical approach to art-making that challenges our notion of authorship based on Western norms, including the importance of a work’s authenticity as made by a single individual. However, Pirambu was actually mirroring indigenous practices of communal working, bringing the community together and giving everyone an opportunity to contribute something new to the process, largely misunderstood for a long time. Chico da Silva’s legacy, recently reappraised, portrays him not only as a painter with remarkable skills and breath, but also as a practitioner for whom working alongside his community was an intuitive outcome of a way of life centered in communal gathering and sharing.

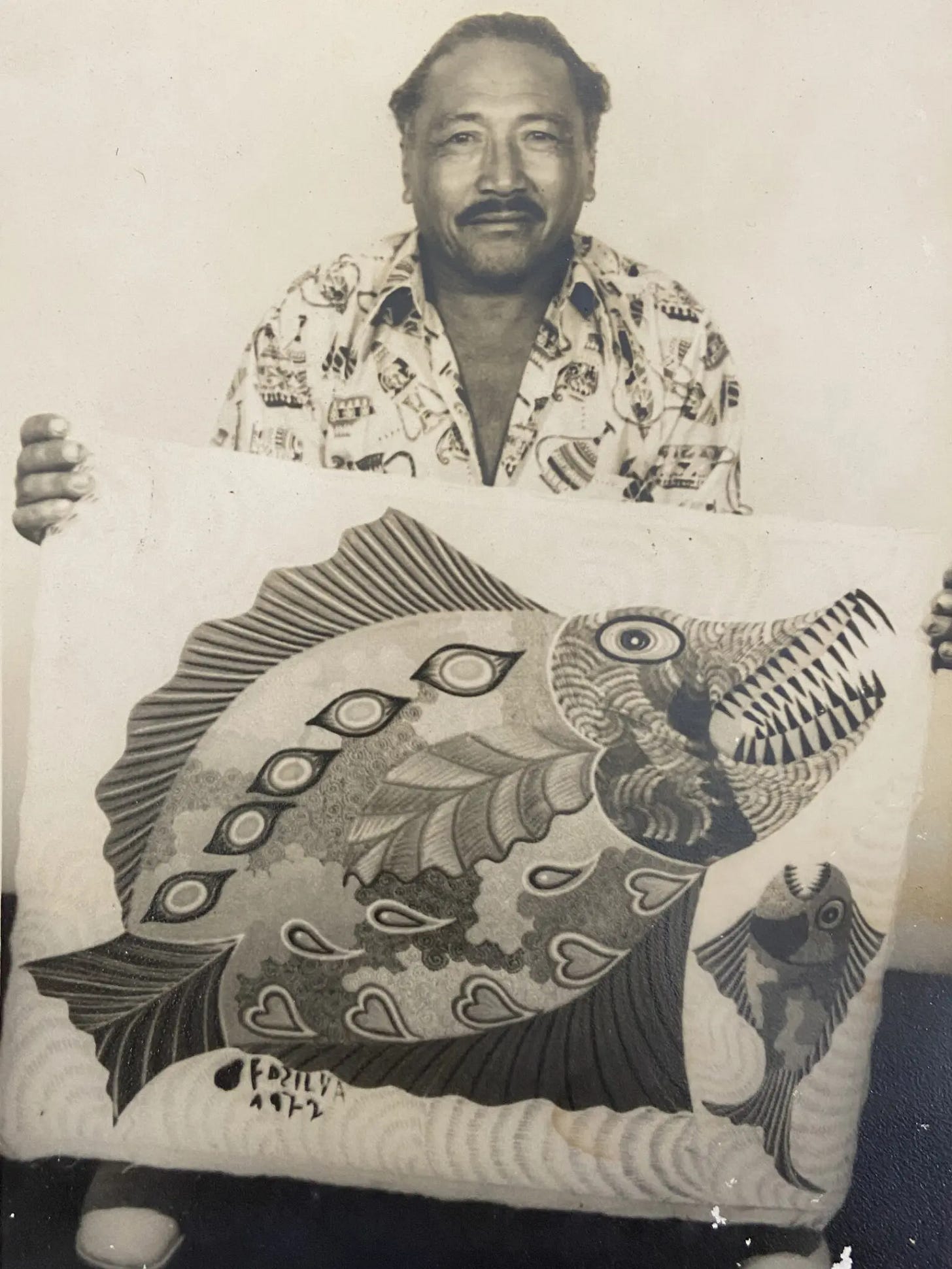

In Untitled (1971), a group of creatures appear to fly like birds, or swim like the titular fish at the center (Figure 6), surrounded by curved outlines resembling waves or clouds that conveniently create a frame for the painting. They convene in an ambiguous setting, perhaps a sea or sky scene. The titular fish rests serenely in the center while an amphibian-looking bird stays very close facing it. Their exaggerated features like elongated teeth and tongues shown through their opened mouths give us the impression they are in deep conversation or maybe ready to initiate a fight. The vivid patterns and colors of the creatures convey a hallucinogenic or dream-like feeling as if Chico is invading one of our dreams or subconscious.

Much of Chico’s imagery alludes to his glorious imagination with an array of creatures standing in for the artist. The predominant motifs, which create intense chromatic vibrations and gestural movements in his paintings, are seen as a reflection of his indigenous roots and culture. The aquatic, amphibian, and hybrid creatures that gather in Untitled (1971) are emblematic of Chico’s distinctive world-building. Imagery of fishlike beings appear frequently in da Silva’s work, probably alluding to the association of wealth and abundance with fish in indigenous cultures, but always with the intent of representing his community.

Chico da Silva has been the subject of numerous solo exhibitions, including the recent large-scale presentation Chico da Silva e o ateliê do Pirambu at the Pinacoteca de São Paulo (2023). Other solo exhibitions include Chico da Silva: Conexão Sagrada, Visão Global, at the Museu de Arte Sacra de São Paulo (2022); Chico da Silva at Gomide&Co (2022); Chico da Silva - O Renascer 100 Anos, at the Centro Cultural dos Correios in Fortaleza, Brazil (2010); Retrospectiva Chico da Silva: do delírio ao dilúvio at the Espaço Cultural do Palácio da Abolição in Fortaleza, Brazil (1989), among many others. His work has been featured in group exhibitions such as O Sagrado na Amazônia at the Centro Cultural Inclusartiz in Rio de Janeiro (2023); Brazilian Fantasies at the International Museum of Naïve Art Anatole Jakovsky in Nice, France (2016); Brasileiro, Brasileiros at the Museu Afro Brasil in São Paulo (2005); 33rd Biennale di Venezia, Venice, Italy (1966), among many others. His work is held in the permanent collections of institutions including the Centre Pompidou in Paris; Tate in London; Pinacoteca de São Paulo; El Museo del Barrio in New York; Guggenheim Abu Dhabi in the United Arab Emirates; Museum of Art in Rio de Janeiro; and the Edson Queiroz Foundation in Fortaleza, Brazil, among others.

For more information inquire below:

Thanks for reading! Subscribe here to receive Artxiom in your inbox each week: